December 2025

Hi everyone. I am just getting back from the annual meeting of the American Meteorological Society, so this blog is a bit delayed. As someone who loves snow and cold, I was excited to experience one of the largest snowstorms in a few years across central Pennsylvania. Unfortunately, that also made travel to Houston more complicated than expected, with 3 cancellations, 2 delays, a broken baggage claim, and a 3:15 AM arrival. What a time. Nevertheless, it was great to catch up with friends and colleagues and spend time engaging more deeply with both the science and how we communicate our work. I also shared some of our recent research on applying climate projections to improve building infrastructure resilience given changes in extreme weather. Feel free to reach out if you are interested. At the same time, I left the meeting feeling even more concerned about what is happening in the field of climate science, particularly the long-term implications for rising students and early career scientists. More on that soon.

This month’s ‘climate viz of the month’ will be brief and focuses simply on annual mean statistics for Arctic and Antarctic sea ice. January is always a busy time of year for me since it involves manually updating many of my graphics to account for the new year. Because most of my visualizations are customized, the transition is not automatic and requires quite a bit of work. I have made good progress though. Many of the figures on my website now include 2025 data, such as updates to my U.S. climate indicators page, so feel free to take a look. If you notice any issues, please let me know! Once the final ERA5 data are available through December 2025, I will finish updating the remaining graphics and share an update on social media when everything is complete. If you have ideas or requests for new visualizations this year, I am always happy to consider them as I continue expanding the collection of near-real time graphics on my site. I am especially motivated to do so given recent federal cuts affecting several climate change data dashboards. I hope these resources are helpful, and if they are, I always love hearing about examples.

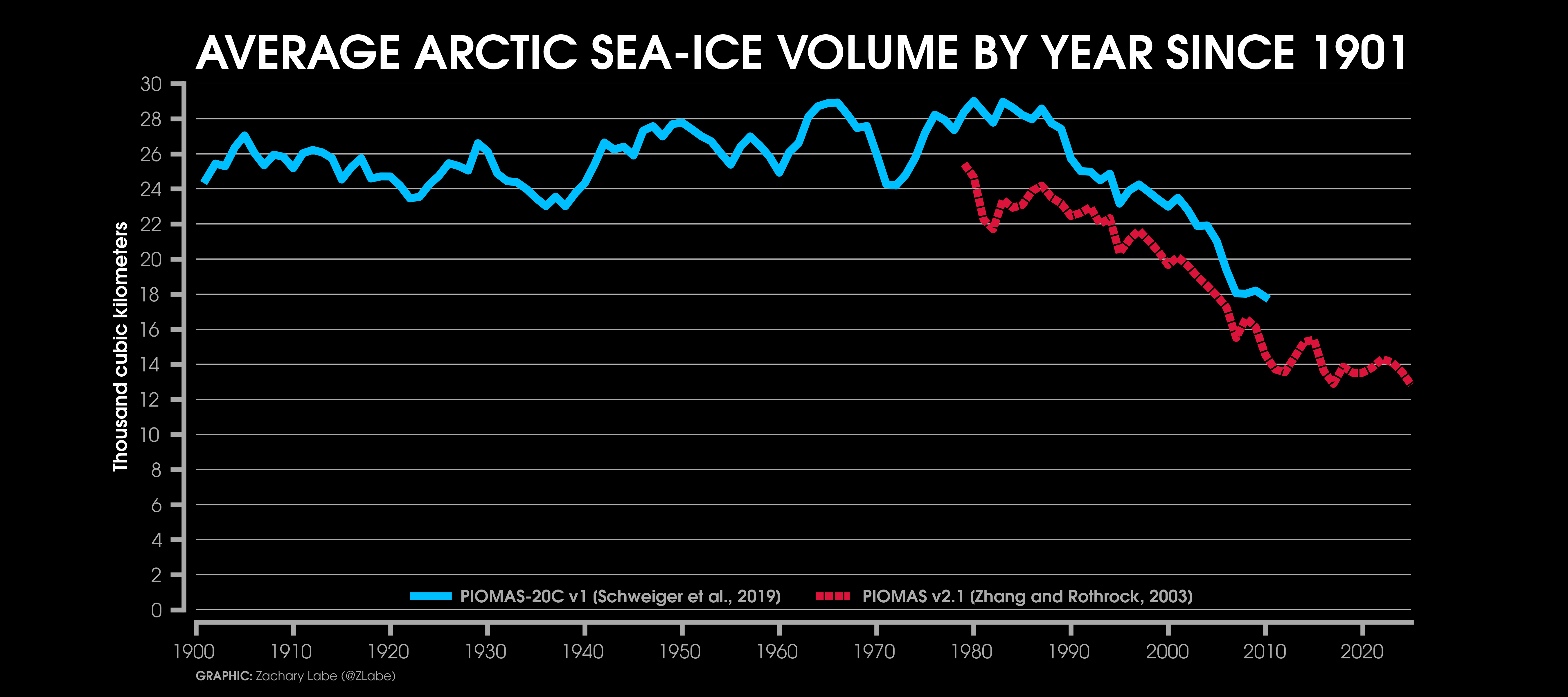

Now for the stats. Annual mean Arctic sea-ice extent in 2025 was the lowest on record, though it’s probably a statistical tie with 2020 and 2016 (rankings can vary depending on the dataset). Similarly, annual mean Arctic sea-ice volume was the lowest (very close to 2017). Despite these technical nuances, the main point is clear: the overall state of Arctic sea ice in 2025 was likely the worst in our satellite-era record. Am I surprised? No. This aligns with climate model projections for a rapidly warming Arctic, and you can explore these model-observation comparisons on my website. Real-world temperature data tracks pretty closely with the model means too. Looking at the PIOMAS-20C reconstruction dataset, 2025 likely had the lowest yearly mean sea-ice volume since at least 1901. This is alarming and has major implications for both our environment and society, and things will get worse without a reduction in human-driven greenhouse gas emissions.

There has been a lot of talk about a slowdown in Arctic sea-ice loss over the past 10-15 years. That’s true, and I’ve written about it before, but it is more noticeable around the September minimum than in the annual averages. Interestingly, annual mean Arctic sea-ice extent still shows a pretty steady decline. Note that 2012 doesn’t look unusually low in the yearly average because sea ice that winter was relatively high before the rapid summer melt, so it balances out. Sea-ice concentration and extent are declining in every month of the year (see trends here), and recall that 2025 also set a record for the lowest annual maximum. Overall, despite less media attention than I think it deserved, 2025 was a really alarming year for the Arctic. Honestly I think many people don’t realize that both average volume and extent set new records…

For the Antarctic, sea ice continued the recent trend of unusually low conditions, which has been the story since around 2016. The annual mean Antarctic sea-ice extent ranked as the 3rd lowest on record, and the annual mean volume was the 5th lowest. These statistics go back to 1979, the start of the satellite era. For this blog, I also included a visualization showing daily Antarctic sea-ice thickness from January through December 2025. This comes from GIOMAS (Global Ice-Ocean Modeling and Assimilation System), a model similar to PIOMAS that I frequently use in my blogs and visualizations. GIOMAS assimilates satellite sea-ice concentration to produce daily and monthly estimates of sea-ice thickness, velocity, growth, melt, snow depth, and surface ocean conditions. It’s a model, so it’s not perfect, but it gives useful insight into Antarctic sea-ice variability and trends. The animation highlights the regional variability of Antarctic sea ice, including its melt, growth, and movement, which are strongly influenced by storms and waves across the Southern Ocean. While many questions remain, like the role of internal variability, it’s becoming increasingly likely that an anthropogenic signal is emerging in the recent Antarctic sea-ice decline.

Finally, looking at both poles together, global sea-ice extent in 2025 was the 3rd lowest on record, while global sea-ice volume hit a new all-time low. Yikes. By the way, some people prefer my combined Arctic and Antarctic graph, so I have decided to permanently offer it here (updated yearly).

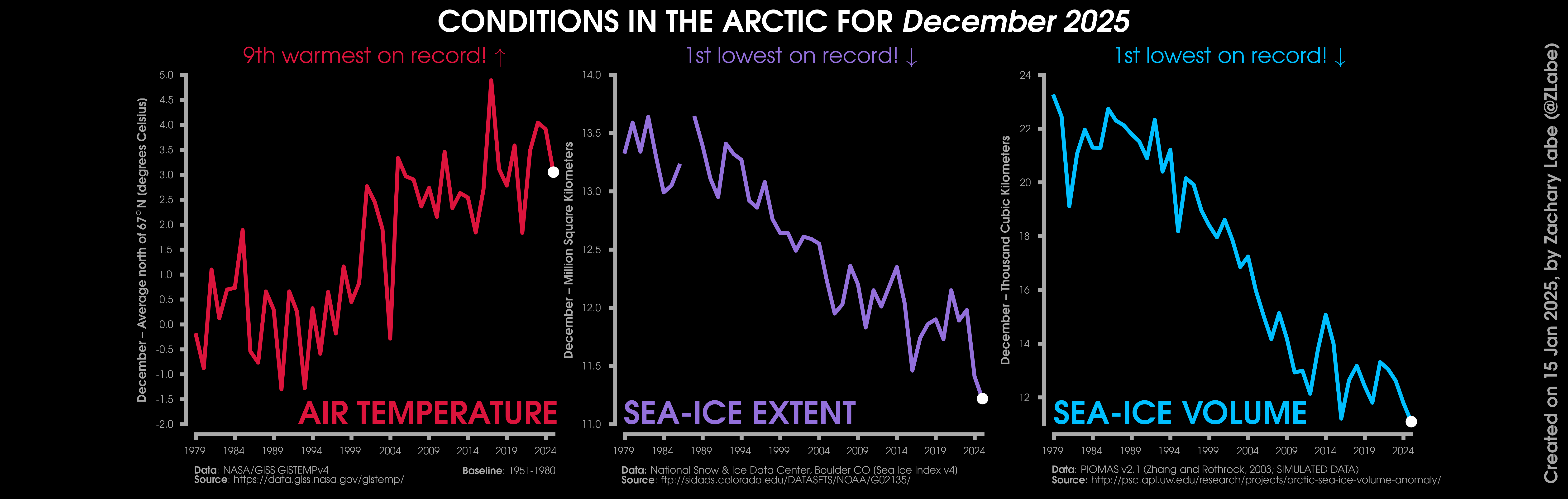

December 2025 was among the top 10 warmest Decembers on record across the Arctic, although the exact ranking depends on how the Arctic region is defined. The highest latitudes (north of 80°N) were near-record warmth for December and continued the recent pattern of large positive temperature departures there. Around the North Pole, anomalies were more than 5°C above the 1981-2010 average. Warmer-than-average temperatures also appeared over the Barents Sea and from Baffin Bay toward Greenland, coinciding with unusually low nearby sea-ice concentrations. At this time of year, it can be difficult to separate causality, since low sea ice can reinforce synoptically-driven warm anomalies by increasing turbulent heat flux exchange from the relatively warm ocean to the colder air above.

The broader temperature pattern featured a clear “warm Arctic, cold continents” structure. Northern Canada and most of Alaska were well below their 1981-2010 averages in December, as was much of central Siberia. In these areas, monthly mean temperatures were more than 5°C colder than average. The persistent cold across Alaska was associated with a large upper-level ridge over the Bering Sea that tends to draw cold polar air into western Canada while pushing warmer air northward over eastern Siberia.

Through the early part of this cold season, the accumulated freezing degree day departure (i.e., simple proxy for overall cold and ice growth) ranks as the 3rd warmest on record. This aligns with the long-term trend of reduced cold season severity in the Arctic. Sea ice in December remained well below average, with new monthly records for both the lowest Arctic sea-ice volume and lowest December sea-ice extent. The previous record low December extent had only just been set last year, which shows how steep the decline has become for this month of the year. Nearly the entire edge of the Arctic Ocean showed less ice than the 1981-2010 average, with the largest negative departures in the Barents Sea, Baffin Bay, Labrador Sea, and Hudson Bay (map of regions). Daily record low extents have also been set frequently since last fall. As I often emphasize, it remains challenging to forecast what the current winter state means for the summer minimum, given the strong influence of short-term weather conditions on sea ice. We still have more than a month before the typical annual maximum, and a lot can change between now and then. So, no predictions from me here.

Thanks for following along! You can explore all of my other posts this past year at: https://zacklabe.com/blog-archive-2025, and browse my archived Arctic dashboard stats here: https://zacklabe.com/archive-2025/. If you would like to support this website, you can also find a Buy Me a Coffee page: https://buymeacoffee.com/zacklabe. More visual climate deep dives coming soon in 2026!

Changes in mean surface air temperature anomalies (GISTEMPv4; 1951-1980 baseline), mean Arctic sea ice extent (NSIDC; Sea Ice Index v4), and mean Arctic sea ice volume (PIOMAS v2.1; Zhang and Rothrock, 2003) over the satellite era. Updated 1/15/2026.

Other Blogs (Monthly):

Other Climate Data Statistics (Monthly):

My Visualizations:

My research related to data visualization:

[2] Witt, J.K., Z.M. Labe, A.C. Warden, and B.A. Clegg (2023). Visualizing uncertainty in hurricane forecasts with animated risk trajectories. Weather, Climate, and Society, DOI:10.1175/WCAS-D-21-0173.1

[HTML][BibTeX][Code]

[Blog][Plain Language Summary][CNN]

[1] Witt, J.K., Z.M. Labe, and B.A. Clegg (2022). Comparisons of perceptions of risk for visualizations using animated risk trajectories versus cones of uncertainty. Proceedings of the Human Factors and Ergonomics Society Annual Meeting, DOI:10.1177/1071181322661308

[HTML][BibTeX][Code]

[Plain Language Summary][CNN]

The views presented here only reflect my own. These figures may be freely distributed (with credit). Information about the data can be found on my references page and methods page.